Episode Transcript

[00:00:29] Speaker A: Good morning, Michael.

[00:00:30] Speaker B: Good morning, Aaron. How are you doing?

[00:00:31] Speaker A: Good. How are you doing?

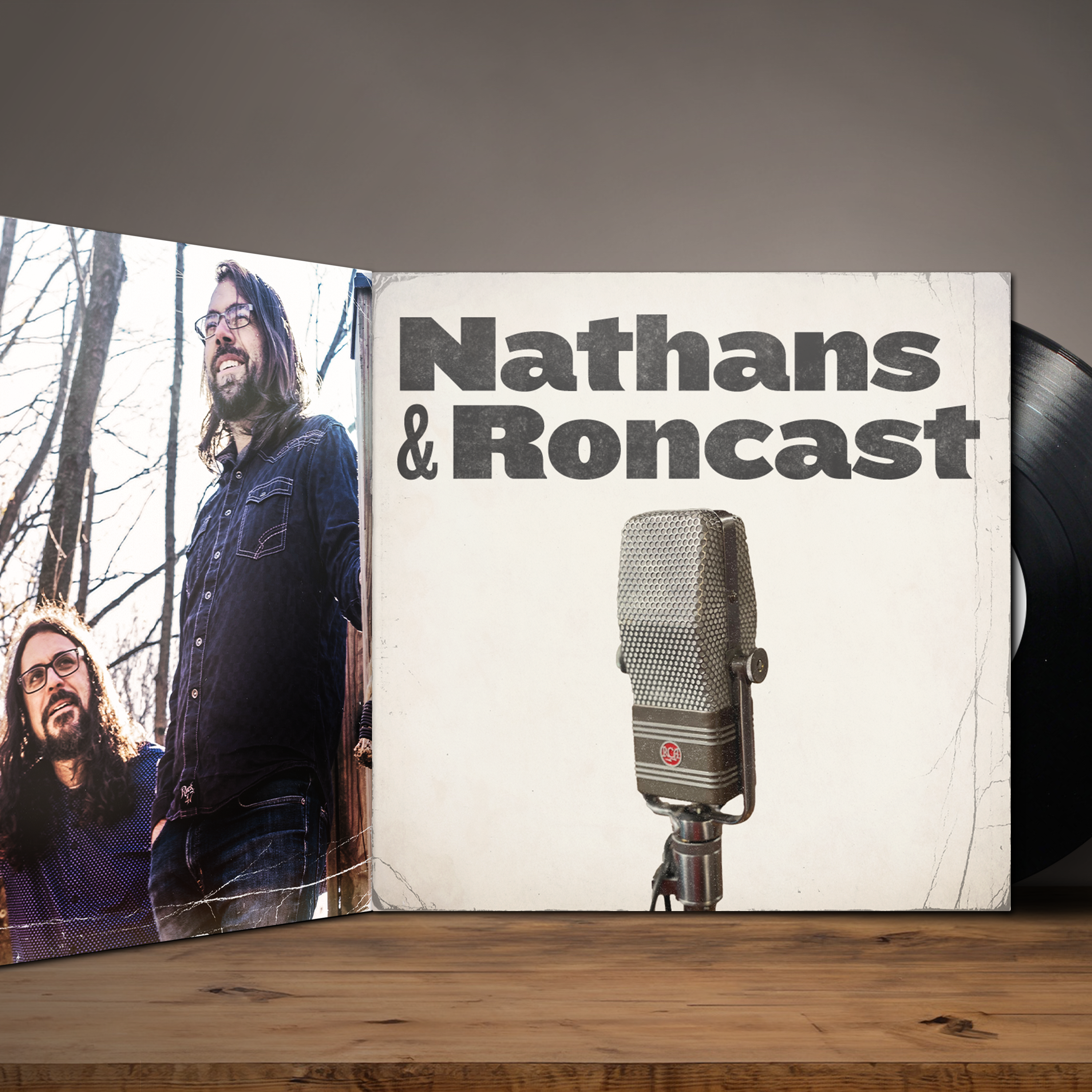

[00:00:33] Speaker B: Good. We're here sitting in a wonderful musical, creative space with Craig Bickhart. And thank you for being here with us on the Nathan's and Roncast.

[00:00:43] Speaker C: My pleasure. Welcome.

[00:00:44] Speaker A: This, of course, is the podcast about the song craft and musicianship, about the songs that we love. And you have written so many songs that we love.

[00:00:53] Speaker C: Thank you. Thank you very much.

[00:00:55] Speaker A: You are a model songwriter. I've learned so much from watching you work. I've copied you from time to time, but failed to even get halfway or a quarter of the way there. But you're a friend, a collaborator for both of us and a neighbor. Thank you for allowing us into your home this morning.

[00:01:17] Speaker C: I'm happy to be here. Happy to talk to you guys.

[00:01:20] Speaker B: So you sent us a number of songs to check out, and one of the things that we try to do is we're featuring songwriters in their craft. That's kind of our main theme or one of our themes. And you certainly have the craft and tell stories and pull heart strings and everything. And the first song that we wanted to kind of touch on was Crazy Nightingale. And to introduce this song, the first time I remember hearing it was at Chaplin's Music Cafe in Spring City.

[00:01:52] Speaker A: That's in Pennsylvan.

[00:01:53] Speaker B: Yeah, in Pennsylvania. But I did a number of shows there with Craig backing him up on cello. And this song always just. It kind of rips your heart out, and you're just, like, feeling bad for the character, but also inspired by the character who's so, like. It's the embodiment in my mind of the struggle of the artist. And I know the subject of the song, but I'd love you to tell us about where it came from and who inspired it.

[00:02:17] Speaker C: Probably when I was in my late teens, I discovered for myself, I discovered the poetry of Dylan Thomas, the Welsh poet Dylan Thomas. And his language is really. It's really intense, really fiery, and it's a sound. It's not just words. It's not just images in poetry. It's the motion of the language. Right.

And so I was fascinated by that and spent a lot of time reading him. And I chanced to find a book about him called Dylan Thomas in America, which was written by a fellow poet named John Malcolm Brennan. And he was charged with getting Dylan Thomas to various reading engagements in America, in New York City when he came over. I don't know the year, but anyway, Dylan Thomas stayed at Brennan's apartment in New York City. And all John had to do was get him to the reading and keep him sober. And so it's kind of a humorous book in a lot of ways. Dylan would figure out ways to get out of the house. He would order food and when the food would arrive, you know, he'd bring it in and then he'd slip out and he'd disappear and they'd find him later down in the bars in the village. And he would go into the bar and he would tell people, buy me a beer and I'll recite you a poem, or Buy me a beer, I'll sing you a song. He had this really beautiful, mellifluous voice. And you can hear him reading like Child's Christmas in Wales and various other things and hear the way he speaks. But it was a wonderful sound. And which, when I was reading the book and reading these descriptions of his voice, it just brought to mind the nightingale. And so that was the core image. And there was a legend that I had read someplace that the nightingale sings by pressing its breast against the thorn. And that's just a folk tale.

And that just seemed to me to be the proper symbol for that artistic torment that a lot of very talented people go through. And Dylan Thomas was sort of, I think he was self medicating that torment with alcohol, which ultimately caused him to have a. I don't know whether the final cause of death was, you know, a stroke or something like that, but it was alcohol induced, basically. He was. I think he was under 40, maybe 39. So I wrote the song with that in mind and trying to tackle that subject of artistic torment, which to me is something that is vastly misunderstood. We have a lot of artists, the famous ones that go Whitney Houston, of course, and back in our day, you know, Janis Joplin and Jim Morrison, Keith Moon and Jimi Hendrix and on and on and on. And then, you know, the same thing happens with actors, movie stars and people like that.

[00:05:12] Speaker A: Jazz artists.

[00:05:13] Speaker C: Jazz artists primarily. There's a big, you know, a lot of them addicted to heroin and die prematurely. But some of this is always credited to excessiveness. You know, just people who can't control themselves.

And as an artist who's been on the road, and I know you guys have toured, it's really hard. I mean, life is difficult on the road. And I think sometimes maybe you do a show and you're kind of wired up, the adrenaline keeps you up at night. And so you take a couple of drinks and before you know it, a couple more and then a sleeping pill and then you're in this spot where you become susceptible to overdose and to death.

Dylan Thomas seemed to be that kind of person that he used alcohol not as well, maybe as a stimulant, but as a way of dealing with the fact that he was struggling, trying to write the poetry that he had written in his youth, as he got older. So the song really kind of deals with that struggle. And there are lots of references to his behavior in the song, but it isn't really a story about him. It's not a story song per se. I don't necessarily write songs that way. So, anyway, that's the story behind it.

[00:06:24] Speaker B: We've interviewed a number of songwriters and asked, you know, Buddy Munlock how he wants to tell a story, and a lot of the other folks we've spoken to. And it's amazing because I think the main thing is that it's not about the story you're trying to tell. You're trying to find an essence of some part of that person or story that you're trying to communicate an idea. So it's not as important to get the.

I'm going to say this story and get all the facts out there.

And, I mean, you see that across banter at concerts, right? You know, we're not gonna give the full introduction of why a song came about, but we might find an interesting aspect of it to lead people into the song so that they're sitting there and wanting to hear the lyrics. And this, you know, this is one of those, in my mind, perfect songs for that, because you can tell the backstory. But then this song also has a life and a story of its own.

I'm curious.

When did you write Crazy Nightingale? And how do you personally feel about the song when you play it?

[00:07:33] Speaker C: Well, it's actually my favorite song. If I had to be remembered for one song, that would be the song. I started writing it, I think, around 2000, 2001. I'm not sure. It took about a year to finish it. Because that thing that you were talking about, that's another thing with me, the difference between a story song and a song like Crazy Nightingale, where the lyric sort of captures the essence of the idea but doesn't tell it in a sequence.

Sequential storytelling is great if you're really good at it. You know, I don't know if I am. I've never really tried. I tend to be interested in certain details about a story. And I'll go back to that when we talk about. If we talk about this Old house. But, you know, the idea that you could tell parts of the story, like the chorus, you know, here's to all the hangers on another round of Alex, you sang your lonely life away, Crazy nightingale. That's the chorus of the song. If you just hear that. What does that have to do with the story of Dylan Thomas? Well, that's what he did in the bars. When he would go down to the bars and do the readings, and he would say, you know, buy me a drink. I'll sing you a song or recite a poem. That's what that. So that's a little scene which is. The chorus seemed to be the touchstone of the song. You know, that sort of life from his perspective, you know, how he felt about it.

But then the rest of the story is mostly just sort of tangential images, couplets, and little descriptive things that link him to that idea of artistic torment. When I got to the second verse, I really had no idea what to do. And that's what took so long. I spent a year. I probably wrote 17 or 18 verses until at one point I was reading the Chinese poet, well spelled Li Po. It might be Li Bai. I don't know how it's pronounced, but.

And he wrote a lot about drinking wine and images of the moon. And I thought, wouldn't it be interesting if these two guys met and had a glass of wine or a couple of glasses of wine together? And so the second verse starts with the imagery of, you know, Li Po.

I've heard of one bird who sang to an ancient age that was in China. He lived in a bamboo cage. That's about Li Po. So bringing these two poets together from different ages and different times, and having them both sort of linked together by the chorus of here's to all the hangers on another round of ale. You sang your lonely life away Crazy nightingale. And that artistic torment being the image of the nightingale sort of, you know, pressing the thorn against its breast, you know, to cause the pain that makes it sing.

[00:10:09] Speaker B: Within my own songwriting, I love grabbing snapshots of moments.

[00:10:14] Speaker C: Scenes.

[00:10:14] Speaker B: Yeah, different scenes, and. And then you kind of find where they go together. Aaron, you did that beautifully in your song. Strength to not fight back. By pulling different figures out of our history and those who have made changes happen in very significant ways, it speaks to the human experience because we see all these people and we think we're so different, and we're just a bunch of humans who kind of do the same thing over and over, in my opinion.

So that's what I think is so beautiful about that.

[00:10:51] Speaker A: Yeah, I Think Craig and I have something in common, is that we do a lot of work on the superstructure of a song. I think, like, as a consumer, when I would hear you play Crazy Nightingale in shows or when I listen to the record, it's. Your guitar playing is so evocative, so beautiful. And of course, I love the sound of your voice that it's easy to let these things wash over you and just. Just be carried in a trance. And it wasn't until the last couple weeks that I'm like, okay, I'm going to dig deep on this song.

And there's a lot there. And, I mean, you could have put any words to that melody, and it would have carried me away. On an ocean of beauty. How important is it to you to make sure to create. You think of an iceberg, right, that you're kind of swimming on top of the ocean, and you see the tip of the iceberg. But to have all that stuff going on under the ocean that people don't necessarily see or notice.

[00:11:57] Speaker C: Right. I agree with that, and I think that's real important to me. It has to create a little world for the listener to step into somehow. And that's done not just with the lyrics. It's done with the sound of. Of the melody and the way the guitar is played. In that case, there's some tuning, alternate tunings going on, the way it's sung, the way it's recorded, the feeling that exists in the song. So all of that has to come together, and melding it or welding it, as you might say, is really what takes the time for me. Because I have to have. You know, I'm not what I consider to be a great singer. I have to have. There has to be other things going on to keep the listener engaged. And part of it is the guitar playing. And so I've got to come up with. Each song has to be based around something really interesting that the guitar is doing. Sometimes it has to be the first thing that I find. You know, I may have a vague idea that I want to write a song called Crazy Nightingale, but until I find a piece of music that seems to evoke the feeling in the idea, I can't do anything with it. I'm not the kind of person that can just, you know, strum C, G, and D and then sing with a really rich baritone voice and tell a story, it doesn't work for me. So most of this is about being the artist that I am, you know, using my limitations skillfully so that I can create something that you Know, I have a palette now. I create the painting and I use the things that I do best, one of which is playing the guitar and incorporating that into the song. So the guitar is not always an accompaniment. Sometimes it's actually the featured. You know, sometimes it's more important than me, my voice and my lyrics and all that. I have to make a statement with the guitar because that's, I think, what my audience expects. Now they've seen me play some intricate things on the guitar and if I do a song where I just strum three simple chords, they're a little disappointed because I didn't do anything fascinating on the guitar anyway, that's in that song. I agree totally with what you're saying. There's almost like a.

This is going to sound weird, maybe to some of your listeners, but there's really a mystical quality to songs. And I think if you don't tap into that, if you don't understand that what you're committ communicating is really beyond language. The language is there to help induce that feeling in the listener. But it's just what's more than that is what's going on. Even with metaphor, you're reaching for something beyond language. You're suggesting images that evoke a feeling in the listener and that feeling might carry them into the melody and the melody might carry them into the guitar part and the guitar part carries them back into the next verse. So you're really constructing, almost like a mini drama. You're constructing a weird.

Michael and I were talking earlier. It's sort of like you're shooting a film and sometimes you have a close up shot, like the opening scene for Crazy Nightingale. It says, once by the White Sea on the rocky coast of Wales, there was a sad sound in the song of the nightingales. What the heck's that about?

But it's a scene. A friend of mine who was a. A poet and a songwriter said to me, you really took a chance with that white sea thing. You know, what is that? And it was just the image, you know, I just saw the waves crashing against the cliffs in Wales. But I have to trust that the listener will get that same feeling from that image that I got. If I didn't get a feeling, I wouldn't know where to go. There's a pretty well known Robert Frost quote from an essay he wrote called the Figure a poem makes where he says, I don't know if I'm quoting it exactly, but no smile in the writer, no smile in the reader, no tear in the writer, no tear in the reader, that's just saying that we have to feel something. So I'm guided by that. You know, if that image comes into my head and I have the language for it, and then I've got something going on on the guitar, and they all kind of fuse somehow, then I know I felt something. The listener is going to feel something.

Songwriting is about faith, right? It's about having faith in what you're doing. Whatever you feel, whatever you see in your mind, you have to, you know, transcribe that. If it's coming from, you know, the great beyond, or from your subconscious mind, wherever it's coming from, transcribe that in such a way and frame it in such a way with the guitar, the voice and the melody that the listener feels exactly what you felt when you had that thought or you had that image. You heard that melody.

[00:16:25] Speaker A: We once talked about about your guitar playing, and you mentioned that it was something that you learned by necessity, that you haven't always. I think you and I were both relatively new in town when we first met about 18 years ago, I think.

Can you talk a little bit about your prior life and why learning to be more versatile with your guitar was necessary to living the professional life you wanted?

[00:16:54] Speaker C: Well, yeah, it's. I'm not a trained guitar player, and I. There are lots of deficiencies, you know, due to that. But when I found a guitar in my parents attic, I think I was about 13 years old, and it wasn't a real easy guitar to play. It was a Stella.

They were made primarily after World War II. A lot of them, the commercial models Stella. But the action was real high. I could slip a pencil under the strings at the 12th fret and push it all the way back up to, like, the fifth fret. Yeah, it was really. It was brutal. And so it was painful for me to learn. But because I taught myself and because this guitar was hard to play, I devised my own fingers. When I. When I got to a point where I saw a Mel Bay guitar book, which was five years after I started playing, and it showed how to finger the chords, I realized, well, I'm doing it all wrong. I'm playing these chords the wrong way. I'm supposed to be using these fingers instead of these fingers. But what I had learned in the process was there were little licks that I could do and little chord formations and little movements and little connective passing tones that I could use because of my personal fingering of the chords. So I never changed that. But that was, again, like I say, I Think my interest in the guitar and my fascination with developing that as part of songwriting was to sort of hide the other deficiencies where, you know, like I'm not a rock and roll singer. So, you know, I was in bands, but I was a harmony singer. I'm not going to wow anybody with my vocal range. I have maybe an octave and a fourth if I'm lucky. The guitar was really important. So my heroes, you know, when I was growing up where, you know, I saw Doc Watson at the main point, blew me away, you know, doing all this incredible finger picking with two fingers. I saw Tom Rush, another guitar hero of mine, who was. This was back in the early 70s when he was still doing those great blues, folk blues arrangements that he was doing to songs. I saw Bruce Coburn, I listened to John Renborn and Burt Jange and that's where I was getting my information about the guitar. And so trying to play some of that stuff, adapt it with my own fingerings because I wasn't playing this stuff correctly. Couldn't figure out how he was playing Angie. And when I was fingering it the way I was fingering, how did he do this? And I realized, oh, he's playing it properly, I'm not, you know, and that was the whole thing. So that, that really became critical for me. I never really saw any separation between the guitar and the singer's melody, you know, and the lyric. It was all one thing. If I had to make that sound, which those guys were making, that was part of the song, you know. And even when I heard James Taylor, his first and second record, obviously there was pop music in there, but it came together around the guitar. There's no way that those songs would exist if James Taylor didn't have that finger picking style, you know. So that sort of became part of me too. What I do sometimes I'll just be sitting around playing the guitar almost half consciously and I'll stumble onto something, you know, just a really nice little introductory lick like Brother to the Wind or whatever. And now I have. That tells me that I have a song to write because I've got this little groove and this little finger picked lick that's going to be the signature, the mode of the song. It's going to grow out of that. And that became really critical. So a lot of my songs, not all, but a lot of them have guitar figures within them that are part of the song. Giant Steps is another one. There's a guitar riff that repeats over and over and the song sits on top of that. That's my way of compensating for the fact that I'm not going to blow you away with the power of my voice or my range.

[00:20:43] Speaker B: Well, one of the things you do is you take your guitar parts and your vocals and the way you present it as an audience member and seeing audience members react, they're like, wow, we love your voice because the way you integrate, where you integrate your voice into your guitar. One of the inspirations, I mean, that doing the melody on the guitar or the finger picking styles leading to a melody that might lead to something that has vocals doing that melody.

[00:21:08] Speaker C: That's right.

[00:21:08] Speaker B: That was a big inspiration for me from what you were doing. I already did it on cello and voice. But when I was like, you know what? I wrote a whole lyric inspired by one of our supporters. Anyway. Basically this Kickstarter supporter gave me a whole sheet of prose about winter but without the cold. And when I saw that phrase, I'm like, oh. And then this whole song just fell out. But it was all based on a finger picking melody and C. And I was like, what would Craig do? You know, and it was, you know, so you're kind of responsible for me not maybe mimicking the way you would play it because I finger pick a little differently, but just, you know, how.

[00:21:48] Speaker C: To construct the song around the song.

[00:21:50] Speaker B: Yeah, let me do that. And I've done that again, like I said, I would do that on cello. I noticed Aaron doing that with his melody and his playing, because Aaron goes between a strumming song or finger picking style and he's got a few things in between. And for me, same deal, like I've got my finger picking cello, finger picking guitar, and then the loud, strummy, let's hit you hard with something. So it's.

At least we have these two modes. And I think that there's a reason why that finger picking style just keeps running our folk music world. You know, it's.

It inspires.

[00:22:24] Speaker C: Yeah, it's sort of a melody inside the song.

[00:22:27] Speaker B: Yeah, yeah. And it's great to have a double. I mean, we. With voices and orchestras, you might have the violas and cellos doing the same melody. Right. You know, well, you can sing and play something at the same time.

[00:22:39] Speaker C: Yeah, that's very true. And that's an interesting topic.

You're not the first person who's told me that pointed it out and recognized it. I used to play the Bluebird Cafe a lot when I lived in Nashville. And one of my friends is Janice Ian, and she used to come out to the Shows. And one night between sets, I came and sat down at the table, and she said, I figured out what you're doing. I said, what do you mean? And she said, well, you play a figure on the guitar, and then you either sing along with that figure or you sing between that figure or you harmonize that figure. And I said, you got it. That's it. That's my songwriting style.

[00:23:19] Speaker B: Those are your options.

[00:23:20] Speaker C: That's the options, yeah. You know, the funny thing is, I could probably take out the guitar and show you if you want to do that.

[00:23:27] Speaker A: Are you in standard.

[00:23:28] Speaker C: Am I wine?

[00:23:29] Speaker A: Are you in standard tuning?

[00:23:30] Speaker C: No, I'm at drop D. Drop D. Okay. Okay. So the song has got this drop D tuning, first of all, with a capo in the third fret.

So the verse goes.

Now I have to figure out what to sing against that. So it's.

And then there's a riff.

So I'm harmonizing that riff.

[00:24:05] Speaker B: Yeah.

[00:24:13] Speaker C: Anyway. Yeah, that's the idea.

[00:24:14] Speaker A: So the point you're making is that. Well, go ahead.

[00:24:17] Speaker C: Yeah. So the point is that, you know, once I've got a guitar part for the structure in the song, then I have to find melodies that either sing between those riffs or on top, they'll double, as you said, Michael, double the riffs. Sometimes they harmonize the rhythm.

And that's just one example. In that song, there's another song where in the world that you've played on that. It almost sounds like a classical piece. But that song, the one that I was just Fooling with, was recorded by Don Williams. And he said, this strikes me as a piece of classical music. And he was a country singer, a country artist who had, I don't know, 20 or 30 number one hits. And he recorded this song, and they put it out as a single, which was really surprising to me.

So it's beyond genre. It's not just, okay, well, that only happens in classical music. It happens in folk music. It happens in country music, too. You know, it's just a way of structuring a song where it isn't just something that's taking place in your head. You know, there's a response between my voice and the guitar. The guitar suggests a melody to me. I start singing a melody, and then the guitar. That suggests a guitar part. So it's a give and take between what my fingers are doing and what my voice is doing. And I think that's really the style that developed. It's not unique to me. I mean, there are lots of other singers, songwriters, who have Done this, but it's one way of approaching songwriting.

[00:25:39] Speaker B: Yeah. Well, thank you for sharing that with us. And it's always nice to know, kind of the inside workings of how it starts. And that's a better way than us asking, so does the melody come first or the music? It's like. No, it's a conversation. It really is.

[00:25:56] Speaker C: I get asked that question all the time. And also, I think it's important to say, too, that songs don't always begin with the first line of the song.

[00:26:04] Speaker B: Oh, yeah.

[00:26:05] Speaker C: I mean, a line will come to me. I don't know what it is. I don't know where it's going or where it came from. But I might figure out that it sounds like part of the chorus. Now I have to go both ways. I have to get to that line and have to get out of that line. Or it might be the third line in the first verse. You know, whatever it is, I have to figure out what that is and then build up to it and come out of it.

And that's just part of. Sometimes songs really just spill out. I've had songs that I've written. The famous story that everybody talks I wrote in 20 minutes. That happens sometimes, but that's very rare for me. Most of the time. I have to spend quite a bit of time, first of all, practicing it so I can play it. And then I have to be able to sing something with it. And the last thing on that song, Donald and June, the last thing that was written was the lyric. The whole song was composed with a guitar part and a melody. And then I had to find a lyric. Now, Aaron and I have done the same thing. I gave him a finished melody and a guitar with a guitar part. And again, in that song, if you listen to the guitar part and isolate that, you'll notice that some of what I'm playing on the guitar is in the melody of the song. But then you had to take that melody completely apart, count the number of syllables in there, figure out where the vowels and the consonants would go. Because the notes that are held, the ahs, have to be vowels, and the, you know, ba, ba, ba, ba. That has to be consonants.

And so that's a really amazing thing to be able to do, you know, to be able to write a lyric to an existing melody. Burt Bacharach did that with.

I don't know how David did it with Burt Bacharach. If you listen to an amazing song and lyric, do youo Know the Way to San Jose?

[00:27:47] Speaker B: Oh, yeah.

[00:27:47] Speaker C: Ellie is a great big freeway put 100 down and buy a car. In a week, maybe two, they'll make you a star. But, you know, listen to the melody alone. And it's a jazz melody. Where did he come up with those lyrics? That's from that old Brill Building school, the.

What was it called? The Tin Pan Alley. Songwriting, you know, and all of that stuff. Fascinating. That's what I grew up on. My father was a big band musician, so that's what I heard the most in my household, was those wonderful songs with really incredibly clever lyrics. Cole Porter songs.

So there's an element in my writing that naturally kind of comes out of that. You can't skimp on anything. When you write a really great song, you're trying to write a really great song. Most of us fail. Most of us the time. There's not a wasted syllable in it. There's not a word that doesn't belong in it. You don't stick the word just in there because you need a syllable. You find a way to put a word that's important there if you can, you know. And that involves reworking the lyrics, reworking the melody, reworking the chord changes. It's a constant interplay of all of this stuff until you get it fused in such a way that it can't be topped. Nobody can take this apart Now I've made it the best it can be. If I hear a song and I hear, you know, throw away words in the lyrics, or I hear just something that melodically doesn't. Doesn't seem like it meters correctly. Now, that's not to say that all songs need to be structured. Lots of songs are very free form, even jazz songs. But you have to get the sense that it's all melded together perfectly.

[00:29:18] Speaker B: Yeah.

[00:29:18] Speaker C: And that's the effort. That's the work that goes into it.

[00:29:21] Speaker B: Do you dare to edit? You know, I don't know. It's like, do you want to. Are you okay with editing yourself? And it's almost like when you've got a collaborative writing situation, everyone has to edit, but when it's just you writing a song, you have to take a moment to edit and look back and then give it space and then edit again just to have the courage to finish it.

And a lot of people say they'll come up to songwriters and say, hey, I don't know how you do it. It takes a lot of courage to get up there and play first of all, and learn something and perform and then also communicate. Like, all these aspects are like a nightmare to a lot of people who don't get up and perform in front of people.

[00:30:04] Speaker C: It's a nightmare to me. I was going to say, oh, yeah, it's really difficult. The older I get, the harder, I'm.

[00:30:09] Speaker B: Sure all of us. I get nervous on stage. I can tell that we all use our nerves for good. That's always what I say, use your nerves for good. Because if you don't have them, it's not going to be very exciting. People I know who don't get nervous sometimes, they're just not as interesting on stage. But those who get a little nervous ahead of time, there's a pack and a punch behind that delivery because trying to figure out how to not fall on our faces. And if we do, we still communicate something, at some point, our mistakes become less noticeable. To the audience, at least, Craig doesn't.

[00:30:46] Speaker A: Look nervous when he's performing.

[00:30:48] Speaker C: That's the act.

That's a complete act. No, I am very nervous. I.

You know, I've learned to deal with that. I think, as Michael's saying, you know, you use it. You know, it goes into the energy that you. That you. That you put out on stage. But I don't think there's a single show that I have ever done where I haven't been like, you know, just kind of a basket of nerves before I walk on stage. Usually after two or three songs, I calm down, but there are still moments in my set, you know, I know that there's a song coming that is going to be a challenge and I have to do this.

[00:31:22] Speaker B: Yeah.

[00:31:22] Speaker C: So it's always that way.

[00:31:28] Speaker A: All right, so this is the end of part one of our interview, and we're going to take a pause here and play the song Crazy Nightingale for you in its entirety.

[00:32:00] Speaker D: Once by the white sea.

[00:32:04] Speaker C: On the.

[00:32:05] Speaker D: Rocky coast of Wales, There was a sad sound in the song of the nightingales above the bright fields.

Yours was the wildest song.

From a dark wood, a plain so clear and strong.

The pale unfettered breast against the thorn how you love to make sweet music pour.

Here's to all the hangers on another round of ale you sang your lonely life away crazy nightingale.

I've heard of one bird who sang to an ancient age that was in China.

He lived in a bamboo cage his voice was silver and yours was smooth warm stone on the sidewalk singing Molly Malone with fiery visions that were fused to be such incandescent poetry.

Here to all the hangers on another round of ale you sang your lonely life away crazy nightingale.

It was always the madness or the drink you were driven to.

I guess in the end, those were the bars you were singing through.

Here's to all the hangers on another round of ale. You sang your lonely life away Day crazy, crazy night in G.